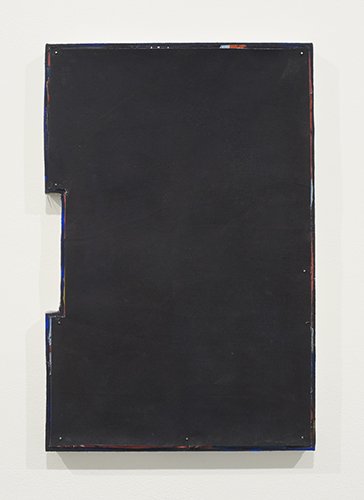

REAL PAINTING

Castlefield Gallery, Manchester 2015, curated by Jo McGonigal & Deb Covell

Artists: Angela De La Cruz, Simon Callery, DJ Simpson, Jo McGonigal, Deb Covell, David Goerk, Adriano Costa, Alexis Harding

Image credits: Cal Carey

Accompanying essay by Craig Staff: Painting qua painting (as noun and verb)

Read this here

ECCENTRIC GEOMETRIC

ARTHOUSE 1, London.

Curated by Jo McGonigal & Deb Covell

Artists: Rana Begum, Alison Wilding, Jo McGonigal, Deb Covell, Finbar Ward, Colin Booth, Shawn Stipling, Patrick Mifsud

(image credit: Cal Carey)

Accompanying essay, by Della Gooden: ‘Eccentric Geometric and theories of the world in our heads’

Arthouse1 presents ‘Eccentric Geometric’ a tightly curated group show, that brings together some of the UK's finest emerging, mid-career and established artists, all with collective concerns that so interestingly justify the show title. Conventional ‘geometric’ issues such as pattern, shape, repetition, line and spatial relationships are ‘Eccentrically’ understood. Whilst acknowledging overlaps with Post-Minimalism, the curators expose explorations of geometry that reveal the complexities and quirks of our lived experience. These artists deploy the principles of geometric order but don’t offer the simplicity of visual sensation alone... there is an empathy with the materiality and physicality of a lived life. This bold, thoughtful show is curated by Deb Covell and Jo McGonigal.

Once upon a time, paint was just another tool of the trade, something artists skilfully applied to a flat surface, to create illusion, to make a painting. The great achievements of representation, with paint playing its magical role, ensured that Painting travelled a long and productive journey.

So when paint unexpectedly broke free of the flat, square structures upon which it had been posited for centuries, its very nature came under the spotlight. Paint’s new identity, and the way it related to the surface, led to new journeys; such as Carl Andre’s, when he decided Frank Stella’s paintings were actually constructions, just like his own sculptural work. He saw Stella’s stripes as a series of single units or objects (the brushstrokes) arranged together on the primary unit or object (the canvas). This was useful to Andre, but at the time, Stella wanted to eliminate Relationality in Painting, he was trying to achieve wholeness. So I wonder how welcome these observations were for his particular journey.

Similarly, when Sculpture borrowed an object from the real world and decided it could still be called ‘Sculpture’ or more particularly, a ‘Ready-Made’ and when it exploded and scattered out from its central, single form, into multiple parts and yet could still be perceived together, as a whole.... the implications were profound.

The Modern Art story is littered with the pioneering particularities and peculiarities of the Name-it-claim-it game; a succession of movements, -isms, manifestos, counter-manifestos and the bold staking out of territory. In reality, these supposed frontiers of practice were often complex pools of enquiry where the edges of understanding can be quite fragile.

In 1966, whilst artists like Andre, Flavin and Judd were getting a turn with ‘Minimalism’, Lucy Lippard curated ‘Eccentric Abstraction’ at the Fischbach Gallery, New York. On declaring the title a semantic convenience, she must have known the word ‘Eccentric’ (not ‘Abstraction’) would intrigue. What was it about this work that she considered uncommon, or perhaps aberrant, to the Abstraction of the day? In fact, many overlaps with Minimalism were acknowledged; Lippard herself wrote that there was a refusal ‘to sacrifice the solid formal basis demanded of the best in current non-objective art’. However, she also took the trouble to declare that artists like Eva Hesse and Bruce Naumann ‘refuse to eschew imagination and the extension of sensuous experience’. The assumption being, that she thought the Minimalists did. She was clear that something else was happening, and that exhibition is now seen as a vanguard for the Post- Minimalists.

The curators of Eccentric Geometric at Arthouse 1 (Jo McGonigal and Deb Covell) choose a title laden with reference to ‘-isms’ and theories, specifically those related to Minimalism, Post- Minimalism and Lippard’s show. At first, after seeing the title, it was the word Geometric that I focused on. It pre-supposes a collective concern for pattern, shape, angle, repetition, line, surface, dimension, spatial relationships etc. However, Geometric, is preceded by Eccentric – and that really is quite a crucial qualifier, because Eccentric Geometric exposes some of those complex pools of enquiry mentioned earlier, where the edges of understanding can be fragile.

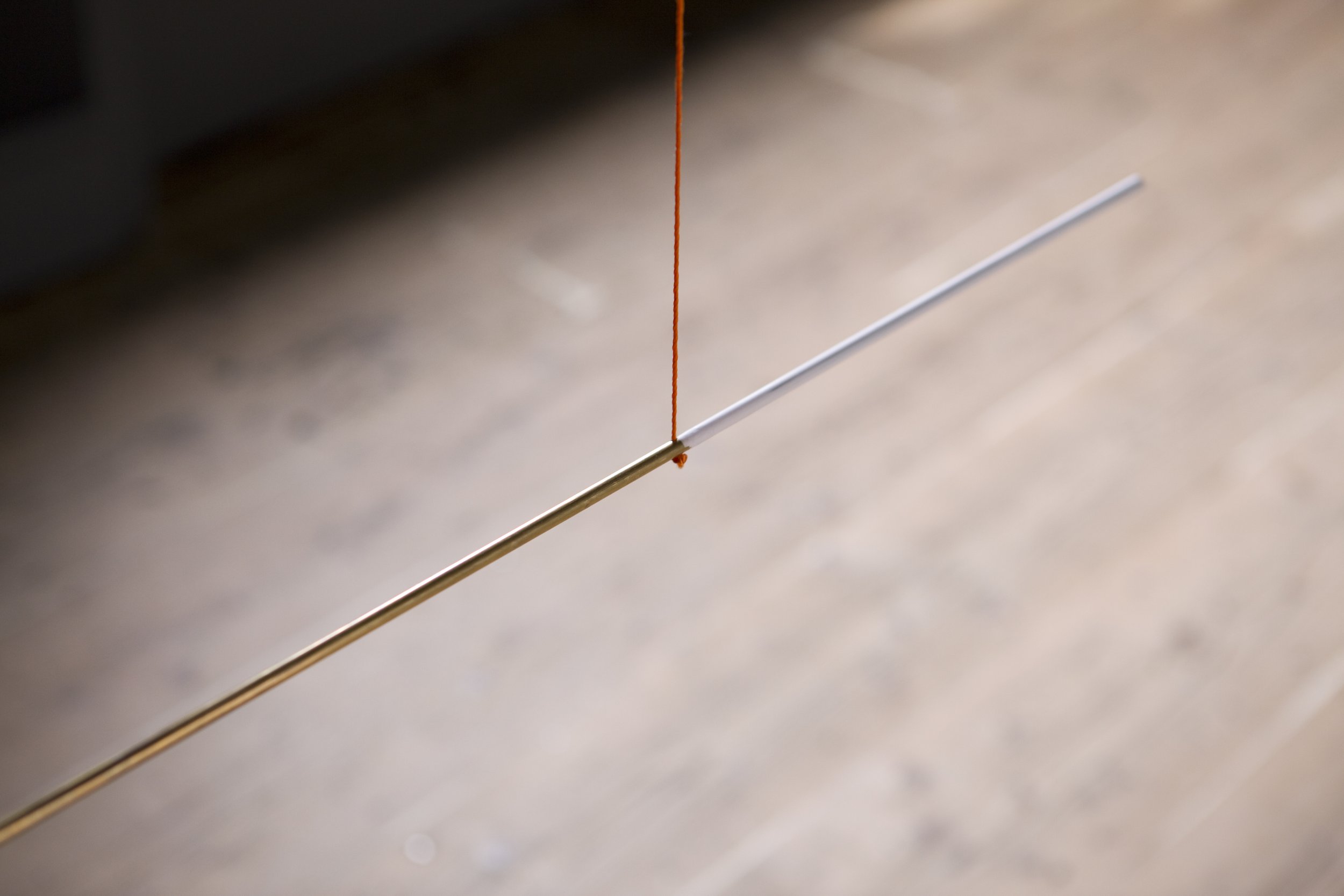

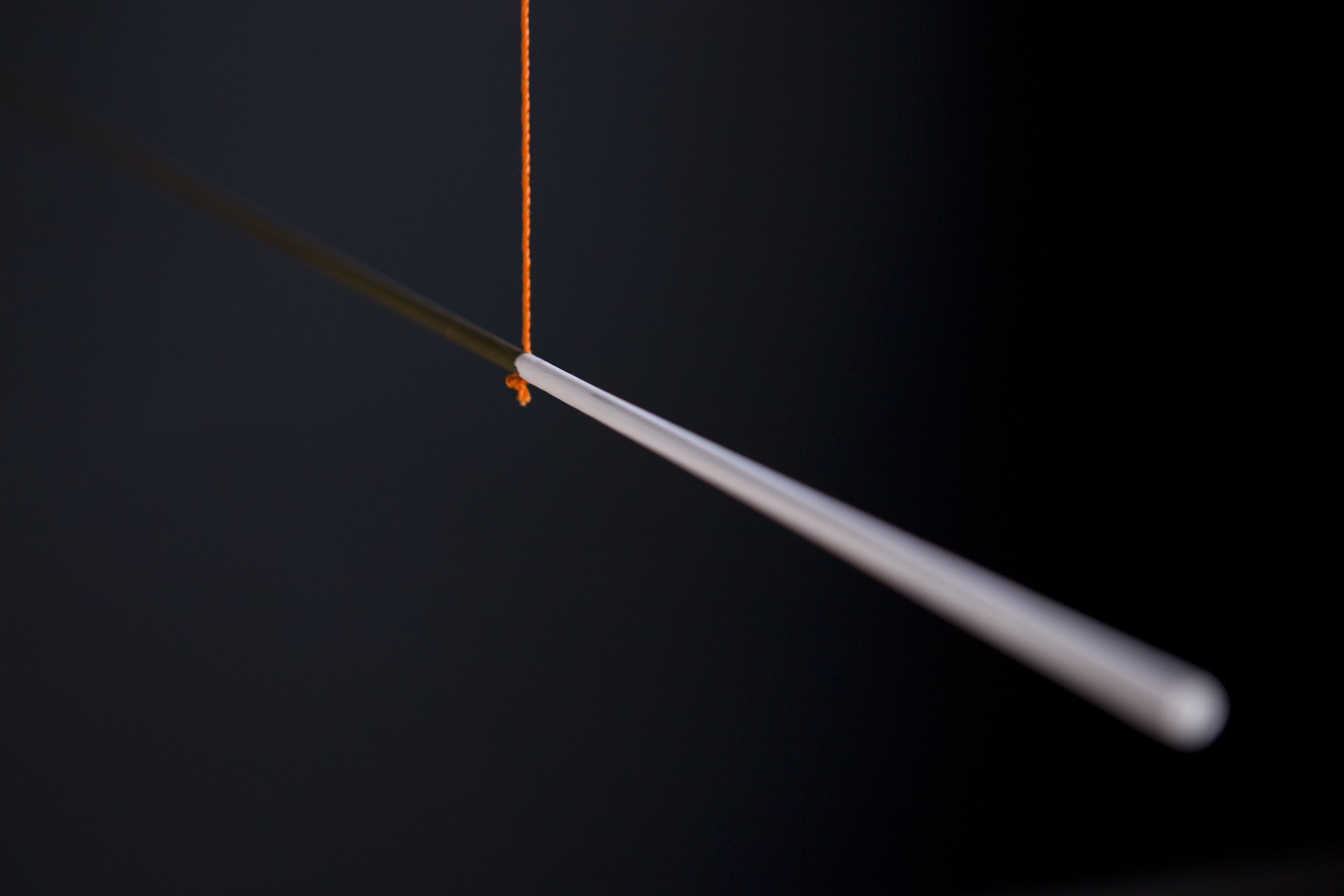

In Eccentric Geometric, Patrick Mifsud’s ‘Fold Series’ (2014) are sturdy metal objects that behave like lines in space. One lays across the plane of the wall, before folding forward, towards me. On completing its circuit back to the wall, it seems to buoy-up air within its embrace. If not

tangible or visible to the eye, this air is palpable to my senses. In Colin Booth’s ‘Gift’ (2010) lines are created by individual white blocks, which sit in a frame, butting up against each other. Functioning as both a unifying and dividing force, the lines consist of nothing. They possess physicality in spite of their lack of mass and despite their need for a lack of light to survive. It appears that nothing, isn’t really nothing; that is until I remove the blocks. When mass is gone, air and shade can’t do the job; the lines cease to exist and the whole piece has new meaning.

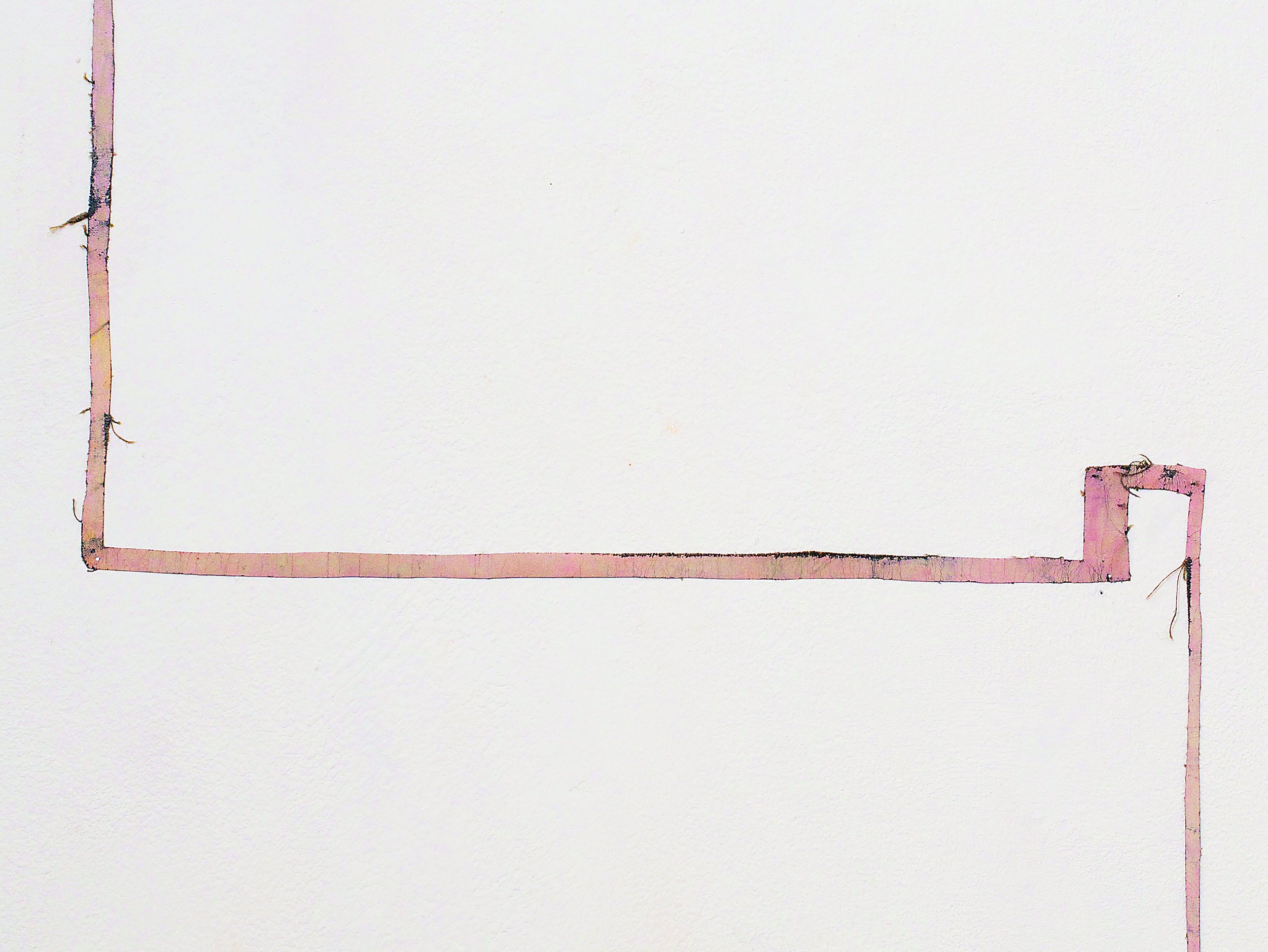

Questions of line also occur when looking at ‘Fold 1’ (2013) by Deb Covell. When two distinct planes meet, are we looking at two edges? Or can we say there is a line? I perceive a line, but I’m not sure it’s fact, if it’s really there. This is not the only curious provision here. Did this piece start out with just one, front-facing surface? Like a painting? And then, after being one thing, was it posed into a second existence? For me it vibrates between two existences because I am so conscious of the ‘act’ of folding whilst I am looking at it; like folding a blanket. And because I can mentally unfold it as I view it, I can imagine what it looked liked before.

This kind of mental interference of the visual experience (which re-runs actions, senses presence in empty space, or re-feels fleetingly, a physical sensation) is something I’m continually encountering here. ‘No. 600 SFold’ (2015) by Rana Begum is inanimate, of course it is. So why do I think it has the potential to move, to flap... even fly away? Why do I need to shift position? Investigate the sides? Why visually measure its weightiness?

Spatial relationships are a part of everyday life. How we move our bodies, how we pick something up, judge distance between objects and place and organise them around us. From laying the table, to standing at the bus stop, all these things add up to a bank of consciousness and perception of the physical world as we, and only we, as individuals, experience it. We are continually expanding what could be described as a ‘theory of the world in our heads’.

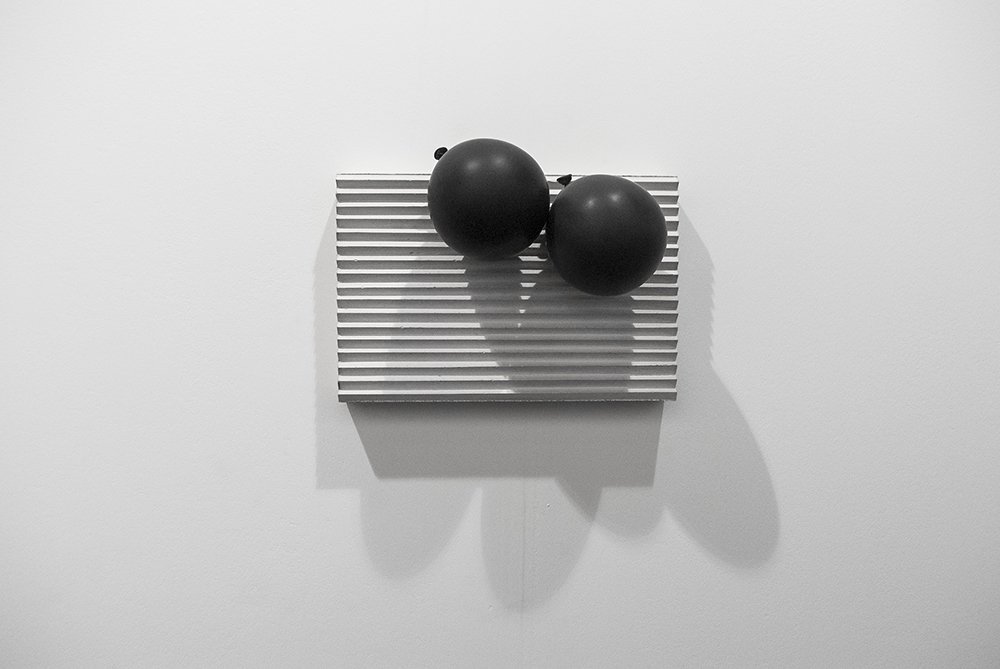

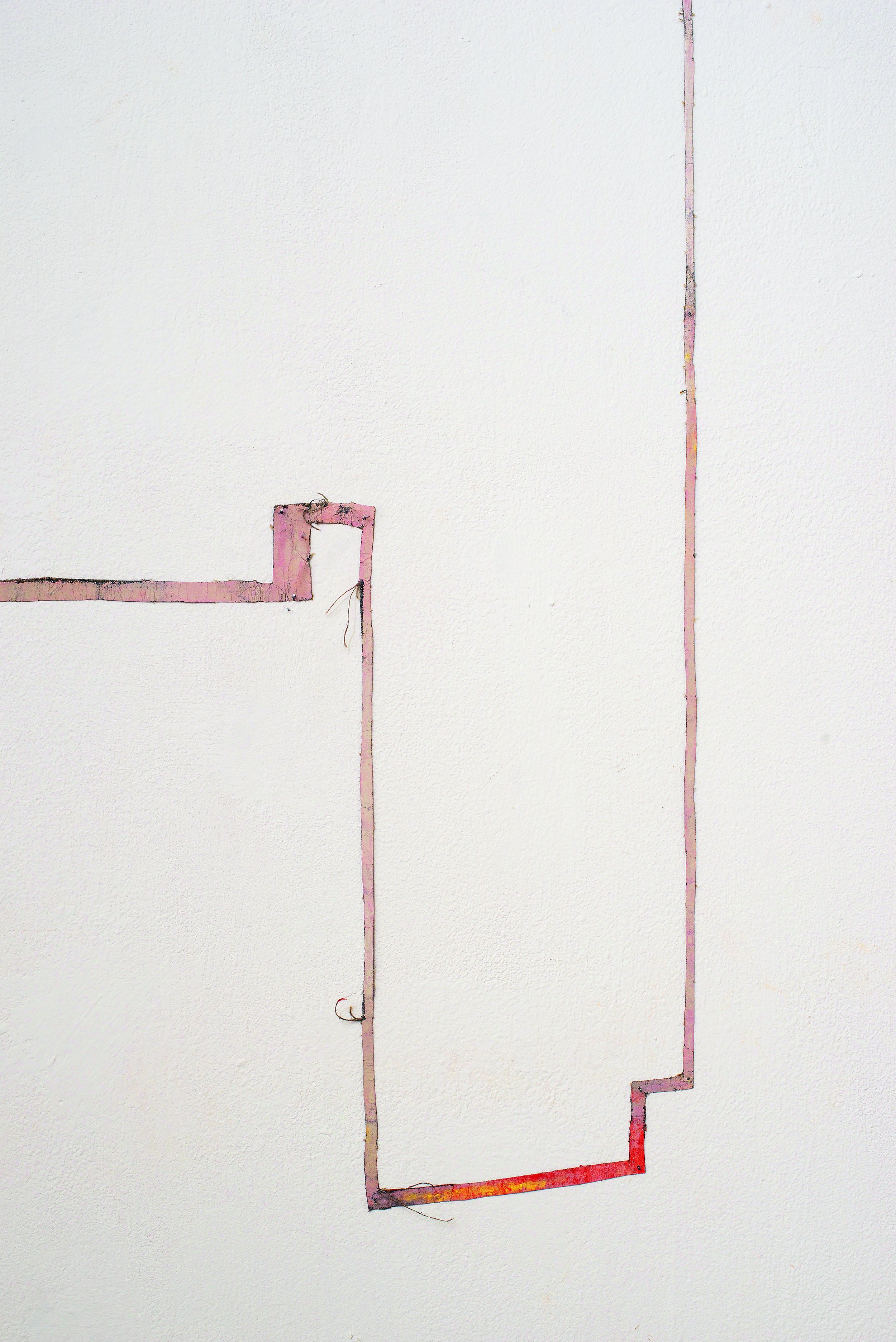

So when I see ‘Aftermath 2’ (2011) by Alison Wilding or ‘Plan’ (2016) by Jo McGonigal, I’m not trying to receive their theories - I’m trying to actualise mine, create my world. The two black balloons that Wilding has upturned and offset against a rectangular surface matter to me. The delicate, battered and broken line that McGonigal traces over the surface of the wall, matters to me. It’s hard to say why or how these things matter, but I think it’s because they fit my theory of the world in my head.

In Shawn Stipling’s new paintings the white lines demonstrate wilful non-compliance. They deliberately slide out of alignment (and I want to straighten them up) They overshoot uncomfortably close to the edges of the canvas (and I want to shrink them down to fit properly) Damn it these lines misbehave with attitude. Or do they? Maybe something else is going on, I have to ask: ‘Is my theory of the world in my head getting an update?

Finbar Ward’s ‘Head Over Heels’ (2017) rests on the floor. When sculpture rid itself of the plinth all those years ago and decided it could sit on the floor, relate to the floor, I doubt it thought this would happen. Ward has upturned the plinth and squashed the art beneath it. The worm has turned. The passive plinth is victorious. This is wonderfully quirky but more than anything it shows that conventional norms and supposed certainties really should be overlooked.

After all, certainty is boring. Make your own world.